What are Crystals? The Makings of the Otoconia and Vertigo

- Ben O'Shannessy

- Nov 11, 2025

- 3 min read

A discussion around vertigo ultimately ends up with a discussion about crystals. Which will often then lead to the question of, what exactly are crystals? The first thing they are is normal. They belong in the ear. It's more about what happens when they don't quite stay put.

What is a crystal?

When talking about vertigo, the crystals referenced are not actually crystals at all. They are something called otoconia. These otoconia are essentially microscopic fragments of calcium carbonate. They also contain otoconin and otolin, with are essentially a protein which helps bind the calcium carbonate together (1,2).

I know, stay with me.

Part of the reason we call them crystals, is their shape. This can be seen in Exhibit A below.

Sizewise, they are tiny. On average they around about 1/10 of a millimetre in size, or 10 micrometers, but can range from 1-30 micrometers (3). As a result, they aren't something you can see with the naked eye (assuming you could get one out of your head) or on imaging like MRI or CT.

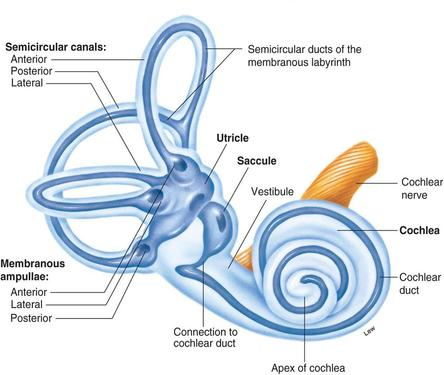

Where do we find the Otoconia?

They reside within a couple of very specific locations within the inner ear, or at least the half of the inner ear that controls balance, the vestibular system. They are essentially glued to what we call the otolith organs. These are the utricle and saccule, which are arranged with one vertical and one horizontal in each ear, as seen below.

What is their purpose?

The addition of a mass of otoconia to each otolith organ essentially makes them able to pick up changes in acceleration by using their weight to detect gravity. Think elevators, cars, aeroplanes, etc. So when I'm in an elevator and it goes up, my body (an subsequently otolith organs) are taken up. Subsequently, because the mass of otoconia is hanging off the surface, they are dragged down by gravity, pulling the hair cells with them. This results in the mechanical force being turned into an electrical signal.

What sort of issues can arise with otoconia?

Probably the most common complication for the otoconia is Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). This is where fragments of the otoconia are dislodged. If this happens there is one of two eventualities - they otoconia fall down into the vestibule (the main cavity where they are located) and dissolve leaving you none the wiser, or they enter the semicicular canals (responsible for detecting head movement) and create symptoms of positional vertigo.

Other issues that can arise relate to changes to the otoconia themselves, both natural and induced. During our lifetime, the volume and number of otoconia are gradually reduced due to degeneration, which also causes changes to their overall structure (4). This process happens with aging (which is why BPPV is more common as we get older), but can be sped up by ototoxic drugs (drugs damaging to the inner ear), infection, and trauma (5). In middle and advanced age the otoconia decrease in number, especially in the saccule (6). There are also genetic differences which can make some people more prone to otoconia changes. Otoconial deficiency has been found to produce head tilting, swimming difficulty, and reduction or failure of the air-righting reflexes (5).

References

Lundberg et al, 2014, Mechanisms of otoconia and otolith development, Developmental Dynamics, vol. 244, pp. 239-253

Zhao et al, 2007, Gene targeting reveals the role of Oc90 as the essential organizer of the otoconial organic matrix, Developmental Biology, vol 304(2) pp. 508-524

Kao, WTK, Parnes, LS, and Chole, RA, 2016, Otoconia and Otolithic Membrane Fragments Within the Posterior Semicircular Canal in BPPV, Laryngoscope, vol. 127, pp. 709-714

Walther et al, 2014, Principles of Calcite Dissolution in Human and Artificial Otoconia, PLOS One, vol. 9(7), pp. 1-9

Lim, DJ, 1984, Otoconia in Health and Disease: A Review, Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, vol. 93(4)

Ross, MD, Johansson, LG, and Allard, LF, 1976, Observations on Normal and Degenerating Human Otoconia, Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, vol. 85(3)

Comments